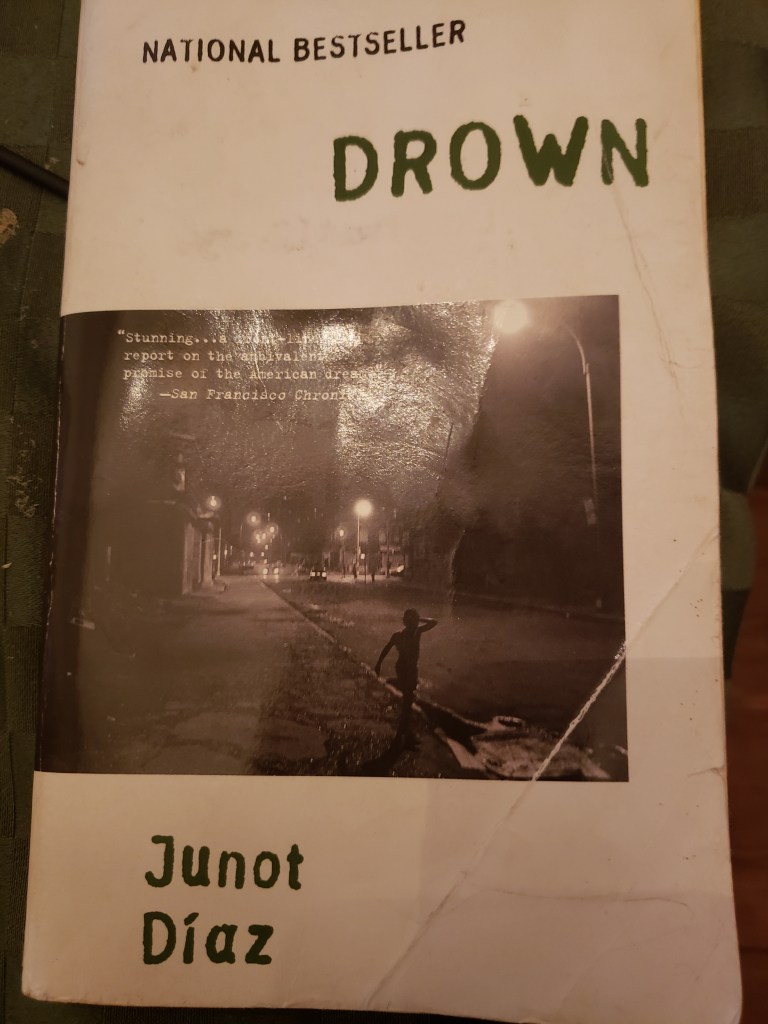

I have a Master’s degree in Spanish which means that I studied the literature of Spain, Latin America and the Caribbean in Spanish. I can still remember the mind numbing 500+ authors on my comps reading list and how even memorizing what country they were from was daunting as half of them had lived in more than one Latin American country in their lifetime. There were like four women on the list and not a single Dominican, which is maybe why when I read The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao in 2008 when Diaz won the Pulitzer for it, I totally fell in love with it. It was very different from anything I had read. It switches between life in the DR under the dictator Trujillo and life for Oscar de Leon, a chubby Dominican American boy in New Jersey who is obsessed with Science Fiction and falling in love. So it’s been twelve years since I’ve read anything by Diaz, and I came across Drown in a free library last week. It’s the first thing he published, a collection of short stories that came out in 1995.

I’d heard that Junot Diaz had been accused of misogyny in 2018 like so many others, but that he had managed to keep his job at MIT but resigned from the Pulitzer Prize board in the wake of cancelled readings and speaking engagements and bookstores refusing to carry his work in response to the accusations.

I was curious about this, but I tend to have a complicated view of the #metoo topic which is so difficult and polemic, it’s nearly impossible to talk about and my mouthing off about how pissed I am that they tried to make House of Cards without Kevin Spacey probably doesn’t help.

So I picked up Drown and started to read it. It also takes place both in the Dominican Republic and in New Jersey. The violence of it really took me aback, and I didn’t remember this in Oscar Wao, although hello it’s about Trujillo so it definitely is there. The first story in the collection is about a kid named Ysrael whose face was eaten off by a pig when he was a baby so he has to wear a mask. All the kids bully him and beat him up and try to make him show them his face under the mask. so the narrator Yunior and his older brother Rafa take a bus to Ysrael’s hometown and befriend him. When they go to a store together to get a drink, Rafa beats Ysrael unconscious with a soda bottle and then pulls the mask off of his unconscious bloody face to see. Rafa turns Ysrael’s bloody, unconscious head using two fingers to get a better look, and then the story ends. And I thought, Good Lord what is the purpose of this? and I stopped reading it for a few days.

and I read news and magazine articles about Diaz instead. Three days before the first woman accused him of misogyny in the form of forcibly kissing her at a party, he published an extremely long essay in the New Yorker, detailing how he was raped as an eight year old boy and this nearly ruined his life and certainly did damage to his relationships with women. People got up in arms because they said he knew the misogyny allegations were going to come out against him so he published this as a preemptive strike. I found Diaz’s essay hard to connect to. I mean who I am to criticize the literary style of someone detailing the effects of a horrifying childhood trauma, but I felt like there was a lot of overused language in the essay, terms that distanced and generalized rather than individualizing…unlike what he does in his fiction which is make the suffering of his characters come alive in a way that is unforgettable. It was actually the contrast between his New Yorker essay on childhood trauma and his stories that made me get why his fiction stories matter so much.

and then all I can find of the allegations is that he kissed someone who didn’t want to be kissed, he yelled the word “rape” at a woman outside a party (this quote is given with no context of the conversation whatsoever) while they were fighting, he called a woman a “prude” and publicly berated her at a reading for 20 minutes because she questioned the representations of men’s treatment of women in his fiction (which, true, is a really unprofessional and asshole thing to do), and finally, a woman he slept with is mad because he slept with her saying he would introduce her to publishers and then didn’t.

It sounds like Junot Diaz, at that time at least, was a bad boyfriend and not a great party companion. So maybe you shouldn’t date him or go to a party with him (or ask him a question about sexism at a reading), but to have an entire country trash your name because you suck at relationships to the extent that they think you shouldn’t read his amazing Pultizer Prize winning novel? Really? It doesn’t appear that he committed any crime.

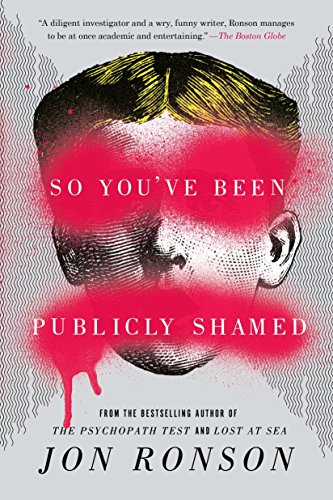

Two dozen feminist scholars in the Chronicle of Higher Education came out to support him and to criticize the media harrassment campaign waged against Diaz. Maybe they had read this interesting book:

Then other people are pissed because why is he being supported but not Sherman Alexie and others? ( I haven’t looked into the Sherman Alexie scandal. I love his writing so much too so you’ll have to give me a minute on that one.)

Details matter. Facts matter. Like this.

Are there people in this country who think she was lying and he was telling the truth? My partner who teaches Women’s Studies said, “It’s not that Congress didn’t believe her. They just didn’t care.”

So my question is does the polemic impossibility of publicly talking about details and facts in these situations really help us to keep a misogynist off the Supreme Court?

I went back to reading Drown. One of the very last stories in the collection is called “No Face” and we meet Ysrael again and hear a story from his perspective instead of Yunior’s and in the last lines are, “He pulls on the face mask and feels the fleas stirring in the cloth…He runs, down towards the town, never slipping or stumbling. Nobody faster.”

Diaz doesn’t leave Ysrael or his other characters in the dirt in their own blood. They may continue to be suffering, but he pulls his literary camera back so far that you can see the biggest picture of how all of these violences are connected and what the implications are for generations and nations of people. We should do the same in real life. Diaz’s characters suffer from all different kinds of violence: racism, misogyny, xenophobia, poverty, sexual violence, dictatorship, addiction, etc. and he manages to make us really feel this through his incredible writing. He writes inside the characters’ experience of that violence in a way that will never leave us. The individuality of the characters and the language takes you into their lives and suffering in a way that is indelible. There’s a heart running through his books for all of his people, even for the men who, out of despair and hopelessness, wreak havoc and violence on the women in their lives.

Having a heart for people who do violence to others as a consequence of their multiple and complicated forms of suffering from structural oppression doesn’t mean we should elect a misogynist to the Supreme Court or not hold people accountable for their violence. It does, however, mean seeing the mutiple and slow ways that genocides are accomplished through generations, and working for restorative justice for these communities.

This is a really complicated issue, and you have treated it with respect for victims & perps–an amazing bit of writing that untangles feelings & issues. I have never read this author, but I intend to now.

LikeLiked by 1 person