My partner Julie went to the protest in Atlanta on Friday night along with about 5,000 other people to stand up against police killing black people and to remember George Floyd and all the other people who have been murdered by the police. Was I nervous about her going to a large public gathering in the middle of a global pandemic? Yes, I was, but I know that it is important and didn’t question her going. She is used to me reminding her before she goes to a protest (in the same way that I tell my seven year old son Tayo every single time he goes out on his bike to watch for cars), that if the police come, she needs to act like me rather than herself and run in the opposite direction as fast as she can. After reading Patrisse Khan-Cullors’, one of the founders of the Black Lives Matter, memoir, I won’t be quipping about running from the police anymore. It isn’t cute, and it isn’t funny. ‘

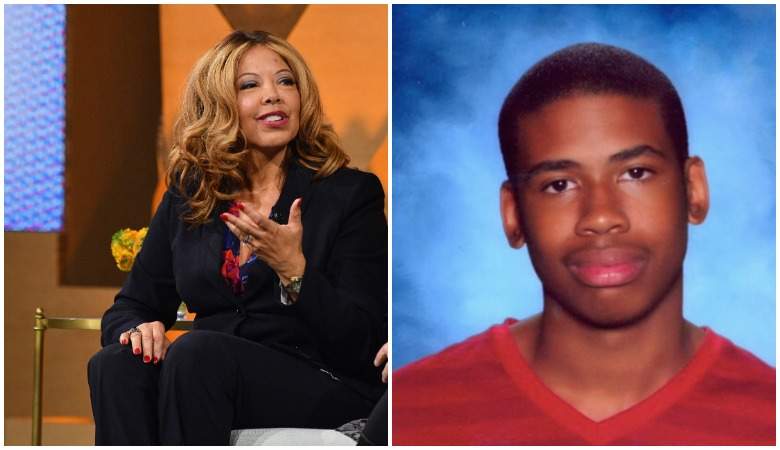

Our son is African American, and when he asked where mama was going, we tried to take a second to tell him quickly that police sometimes kill black people in this country because of racism and mama is going with a lot of other people to say that this isn’t ok. We don’t talk to him about this trauma too much, but I hear the voices of black friends telling me that not educating him on this topic isn’t a choice I can make. Tayo definitely doesn’t want to hear it. He is upset that his friend Leo has just stopped riding bikes with him because he had to go somewhere with his parents. We try to gently say one more educational sentence about the police, and he says, “but they come to our school to be our friends.” We leave it with, “some police are good and unfortunately some aren’t” because you can’t explain to a seven year old that policing is a system that is designed in its origins to oppress black people and people of color regardless of the nice, loving individuals who work within that system. I don’t fixate on him potentially being in danger in the future because I can’t. I don’t even want to talk about it, and I live in the idea that our white privilege and class privilege will protect him, and I would rather not have someone argue against that to me. (Go ahead and say to me that the fact that I can think for even a second that I have less chance of getting killed because of the color of my skin and income and that I desire to pass this onto my son shows that the world we live is created out of violence that I benefit from.) My staving off terror with the sin of privilege was interrupted when Tayo was little by a daily reminder of the murder of Jordan Davis, a 17 year old high school student who in 2012 was in a car with his friends playing hip hop music at a gas station in Jacksonville, Florida . When he was told by Michael David Dunn to turn the music down and Jordan refused, Dunn shot and killed him. When Tayo was four and five years old, he refused to listen to any music in the car other than hip hop and every day he demanded that I roll the windows down and turn up the music. Jordan’s mother Lucy McBath, is a US congresswoman who represents George’s 6th congressional district. She became an activist after her son’s murder and continues to fight for better gun laws (which means any gun laws, right?) in the US.

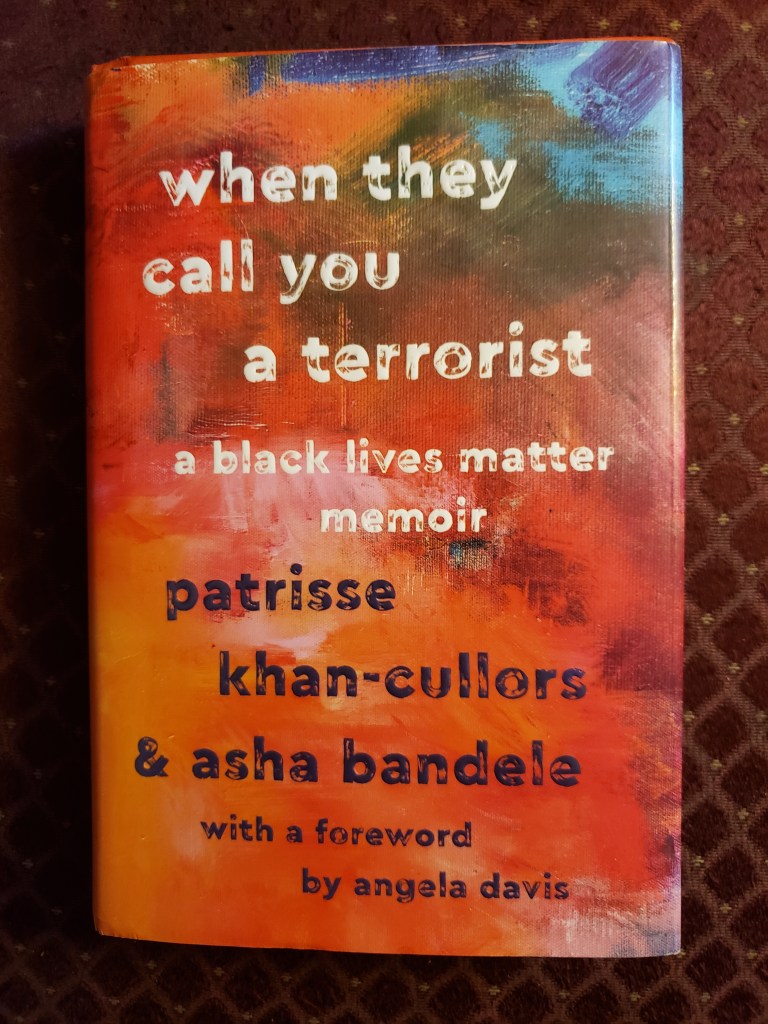

So I decided to try to kick my privilege in the butt for a minute by reading Patrisse Khan-Cullors’ memoir even though I didn’t want to because I hate thinking about the topic of police violence and racist incarceration. I am so glad I did read this book. It really helped and changed me. I need to have all these facts wrapped around me so I wrap myself in truth rather than in fear and the racism that my whiteness will protect my son.

Khan-Cullors tells the story of her family and her life. She lived in Van Nuys, California, and her community, family and friends lived under constant state funded violence through the police. Her older brother Monte began to be harassed and arrested for just talking to his friends from the age of 14, and later, as his schizoaffective mental illness developed, he was repeatedly tortured within the prison system. Khan-Cullors’ father, Gabriel, was also incarcerated …..She herself was arrested for the first time at 12 years old for smoking weed that she got at the predominantly white school she attended where those students never experienced fear of arrest ever, even for dealing.

It’s hard to synopsize the very important education Khan-Cullors offers in her book about the war on drugs (white people have always used and sold more drugs than people of color), gang legislation, the ACLU’s 86 page complaint against the LA County Sheriff’s department for torture and other very detailed and factual examples of planned, premeditated, organized, well funded initiatives to eradicate the black community. But I will try to highlight a few things. She starts chapter one with a quote from John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s National Domestic Policy Chief, “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be…black, but by getting the public to associate the …blacks with heroin…and then criminalizing (them) heavily, we could disrupt (their) communities…Did we know we were lying? Of course we did.”

The language of terrorism (The title of this book is when they call you a terrorist) is never used against white people. It is used to demonize people of color. When Nelson Mandela wrote about the conditions of life in South Africa under apartheid which Khan-Cullors cites, you will see that there is very little difference between what he is describing and what people in Van Nuys and many other parts of our country are living through today. Mandela was on the FBI’s list of terrorists until 2008. For having come up with the phrase #blacklivesmatter and then organizing with it, Patrisse Khan-Cullors is likely still on that list and will remain on it. She doesn’t say that in her book, but I am guessing it is true. She does detail having her home raided by a SWAT team in full riot gear with helicopters overhead.

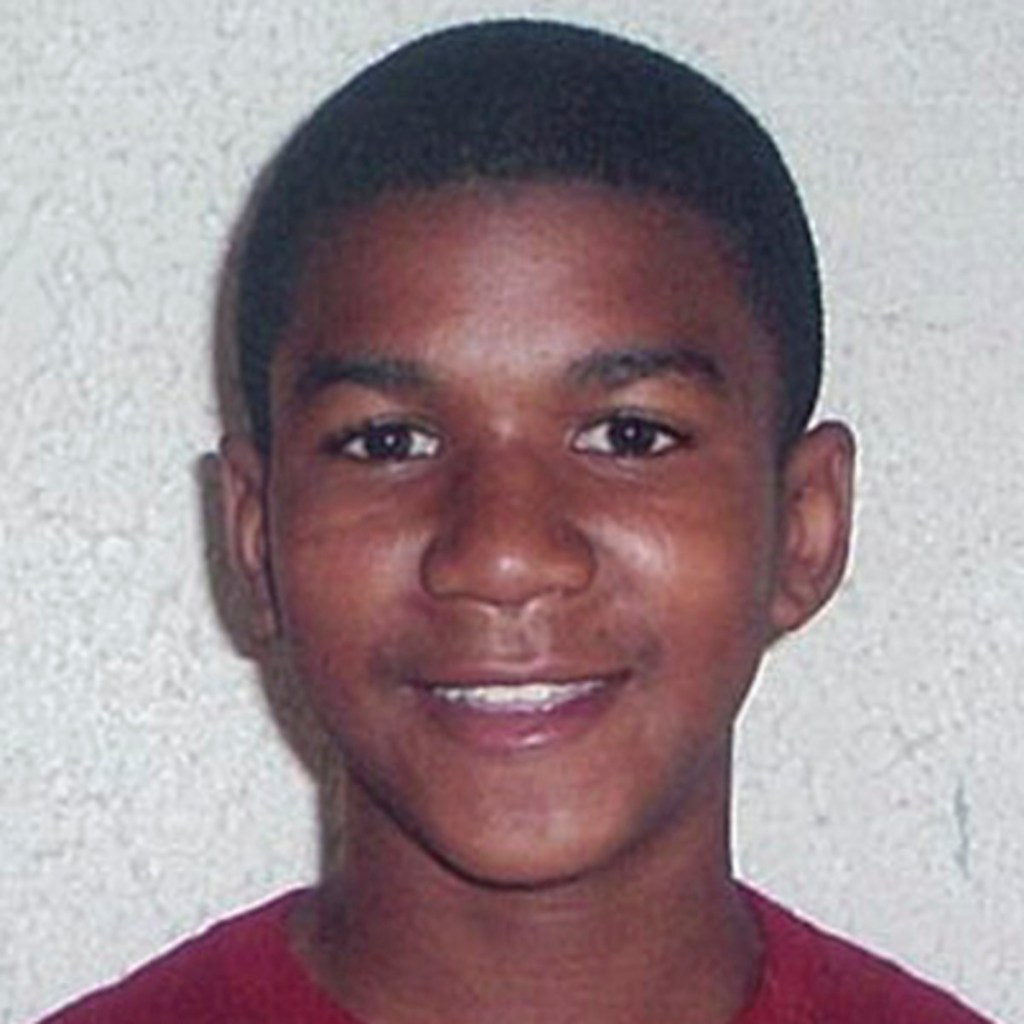

On Feb 26, 2012 in Sanford, Florida, 17 year old Trayvon Martin was walking home, carrying an iced tea and a bag of skittles for his little brother, talking on the phone, comforting a girl who was experiencing being bullied, and George Zimmerman shot and killed him because he was black and wearing a hoodie. Zimmerman was acquitted, and when Khan-Cullors exploded into grief when she heard the news of the acquittal, in a message exchange with Alicia Garza (a co-founder of BlackLivesMatter along with Opal Tometi) she wrote the phrase #blacklivesmatter.

BlackLivesMatter organization and activism expanded in Ferguson, Missouri after the Aug 9th, 2014 murder of 18 year old Michael Brown by the police officer Darren Wilson who was not indicted and cleared of civil rights violations by the Department of Justice.

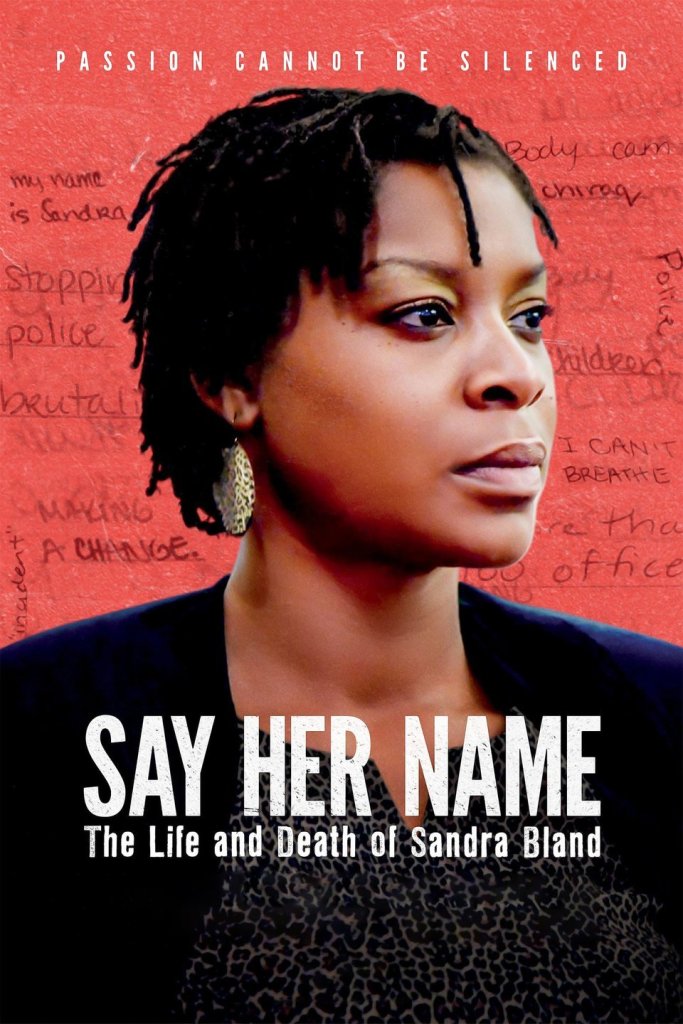

Khan-Cullors remembers many victims (including women and girls) of police murder in her memoir: Renisha McBride, John Crawford, Eric Garner, Tanisha Anderson, Miriam Carey, Shelly Hilliard, Rekia Boyd, Shelley Frey, Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Kathryn Johnston and others and goes into detail about the death of Sandra Bland in jail in Waller County, TX on July 13, 2015 who inspired the slogan #sayhername.

I feel stronger from having read Khan-Cullors memoir because it is so clear. Today there is less noise in my head about my fears, my privilege, jokes about running from the police. There is a certainty filled with facts about the genocide of slavery that this country was built on and how it has just shape shifted into different insidious forms. I have never written anything like this before, and in fact have never verbalized the fact that I have rested in the hopes that whiteness would protect my son. But the intensity of national action against racist murder has shaken it loose in me, and I can’t hold on to it anymore. I can’t exactly tell you who I will be or what I will do when I hit Publish on this blog and go on with my life, but I know it will be clearer and more committed thanks to this weekend’s events and from having read Khan-Cullors’ memoir.