I am really interested in genre studies. When I was a middle school English teacher, the text book I used had an excerpt from The Diary of Anne Frank as well as a story and a play version of the diary.

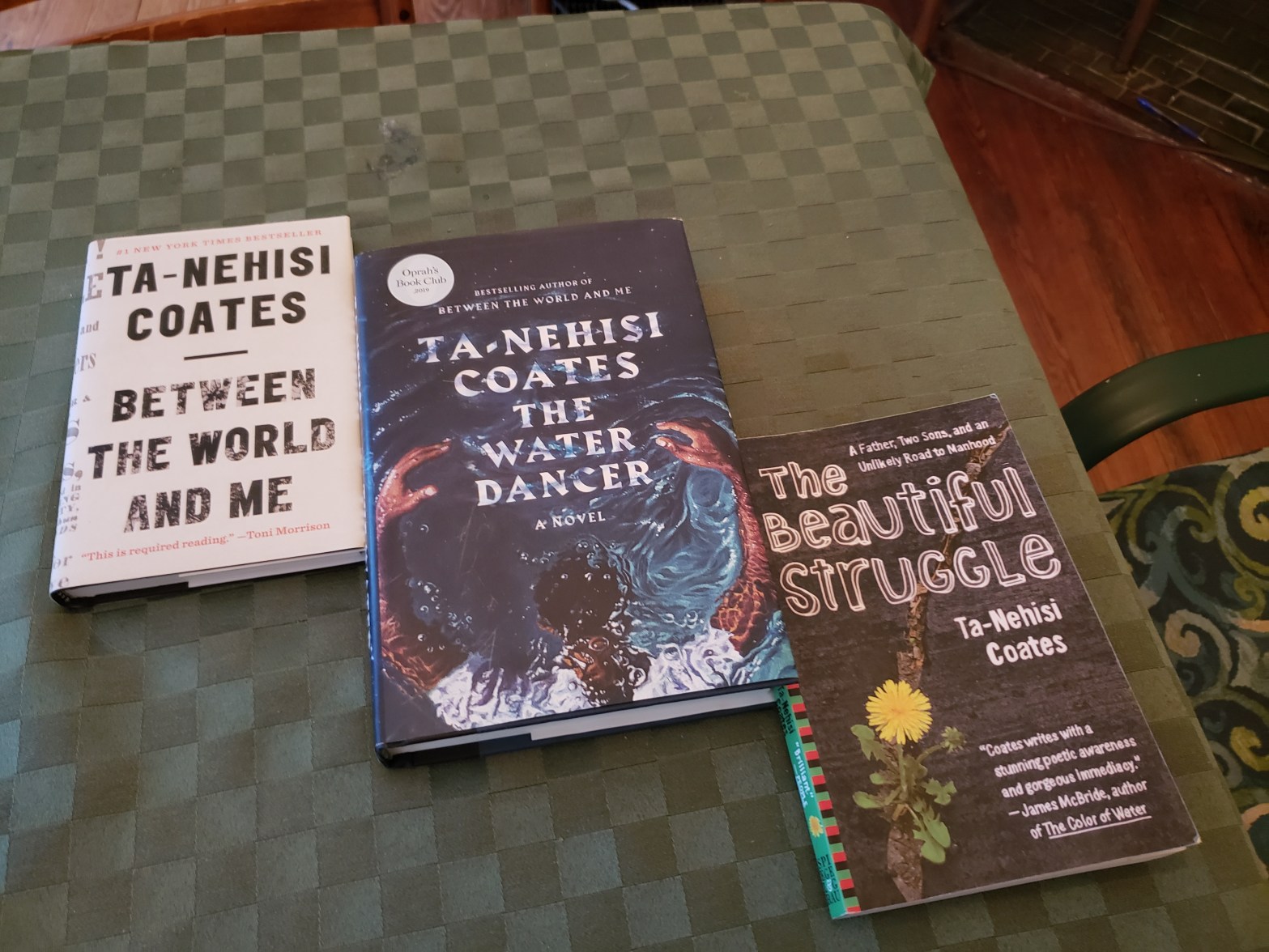

I was excited about my lesson plans. At the end of it, one of my brightest students said that it was way too much Holocaust at once and that she found it emotionally overwhelming, which is of course, legitimate. Honestly, I hadn’t even thought about it because I was so into the idea of finding hidden ways into the story or stumbling into deeper understandings of the characters’ thoughts and lives through exploring the unconscious clues, additions, repetitions and contradictions in a story told in three different ways. I stumbled into just such unexpected insight this week when I read three books by Ta-Nehisi Coates. If I had only read The Water Dancer (2019),

an incredible novel about a slave who comes to work for the Underground Railroad, I am sure I would have liked it, but it would not have made me feel profoundly transported into the world of the past in a way that directly informs the present, had I not read Coates’ other two books first.

The Beautiful Struggle (2008) is a memoir about Coates’ life as a teen in West Baltimore where he was afraid of being killed every day by other teens with guns on the way to school. His father, a Black Panther, scholar, historian, and conjurer of the dead texts of his people who runs a printing press out of his basement to revive the lost histories of the African diaspora, imparts community and history to his sons to try and provide them a way to save themselves from the violence. You understand in this book that there is a direct connection between the past and the present and that centuries of racism create a disembodiment and hopelessness in communities that are afflicted by violence and the genocide of mass incarceration today. “I was not in any slave ship. Or perhaps I was, because so much of what I’d felt in Baltimore, the sharp hatred, the immortal wish, and the timeless will, I saw in Hayden’s work (poetry about slavery) and that was what I heard in Malcolm…” (Between the World and Me, 51)

Between the World and Me (2015) is a letter to his adolescent son for which he won the National Book Award. Like his father before him, Coates is trying to impart hope and protection to his fifteen year old son Samori in the year that his son saw the killings of Eric Garner, Renisha McBride, John Crawford, Tamir Rice and learned that the police who killed Michael Brown would go free.

Coates writes to his son, “I have raised you to respect every human being as singular, and you must extend the same respect into the past. Slavery is not an indefinable mass of flesh. It is a particular, specific enslaved woman, whose mind is active as your own, whose range of feeling is as vast as your own,..who prefers the way the light falls in one particular spot in the woods…who loves her mother in her own complicated way… Never forget that we were enslaved in this country longer than we have been free.” (250 years) p. 69-70

This is what Coates does in The Water Dancer. He writes characters that are living, breathing people and in doing so he performs a fictional “Conduction”. Hiram Walker, the main character, develops throughout the novel, his capacity for Conduction which is the ability to transport people into another place by going back in his heart and his mind into a profound collective memory of the horrors and pains of his people and allowing them to come alive in him in order to transport others to freedom. So not only do you the reader get to see conduction happening, you experience it through the process of reading the novel. The other character in the novel who is able to facilitate this transformation for people is Harriet Tubman, also known as Moses.

The Water Dancer in its depiction of Conduction has elements of “magical realism” that might turn some people off by causing their mechanisms of suspension of disbelief which are necessary to get immersed in the fiction to fail. In other words, you are reading along, captivated so that you believe you are in the mid 1800s in Virginia when something magical happens that you don’t believe is possible so it throws you out of the fictional world in an unpleasant way. This could have happened to me if I hadn’t read Coates’ other books first. In Between the World and Me, he writes about his atheism and his struggles with the perceived salvation in another world passivity of Civil Rights luminaries that were held up as models in his classes. “How could they send us out into the streets of Baltimore, knowing all that they were, and then speak of nonviolence?” (32) I don’t need someone to be an atheist in order for me to believe them, but by the time I came to read The Water Dancer, I was so attached to Ta-Nehisi as a person through his impassioned, young, honest, adolescent self in The Beautiful Struggle and the grounded, unflinching, unapologetic father in Between the World and Me that I trusted him to transport me to another world that I might have balked at if I didn’t feel connected to the author. Therefore, I allowed myself to be “conducted” to 19th century Virginia in fiction and in life.

A friend of mine who is a wonderful, loving person who spends a great deal of his spare time doing important anti-racist community building work for children and families comes from opulent slave owners in Virginia. I also come from slave owners in Georgia but have never really had this impact my understanding of the world except for a vague sense of guilt and injustice. Right before I read The Water Dancer, my friend told me that he had brought actual 19th century ledgers from his home in VA (because his family has held onto everything and has not yet donated them to a museum) that listed the names of slaves that were owned by his family and how much they cost and how much they sold them for. There are pages and pages and pages of these names. He texted me pictures of a couple of the pages, and I looked at them again while I was reading Coates’ novel. I held onto them as an article of “conduction” so that I could try to connect with my ancestry and the rape, murder, and annihilation of families for economic profit that are the foundations of our country that led to generations of wealth that I still benefit from and generations of trauma and poverty where disembodiment and violence continue to rule the lives of communities in West Baltimore and many other places.

I know some white people don’t want to do this and don’t see the point of connecting to their slave owning past. I know that it can cause an angry reaction of “That’s over…the past is the past..why are you dragging all this up that is dead and gone and doesn’t have anything to do with me???? I didn’t own slaves!!!! Get over it!”

But we need do it for healing. Because in the same way that the past is alive in choke holds on black communities, it is also alive in choke holds for white people. We profit from this choke hold, but it is killing our hearts. Imagine a rich white person whose profits directly or indirectly come from the exploitation of the labor and lives of people of color. You picture a deeply happy, fulfilled, loving, thriving person, right? So no… We need the healing and going out into the streets is a great start,

Now that we have hope because hundreds of thousands of people have stood up in countries all over the world to say they care about ending racism in the United States, white people can feel brave enough to go another step further and engage in our own historical conduction by imagining the singularity of our slave owning forebears and its legacy for us. In The Water Dancer Hiram’s father is his owner. Racial violence is incestuous violence. It happened and is happening in our family, not some separate, removed place. I know we have spent the last 155 years trying to pretend that these atrocities are happening somewhere far removed from us, but it is in our house, our families, our lives.

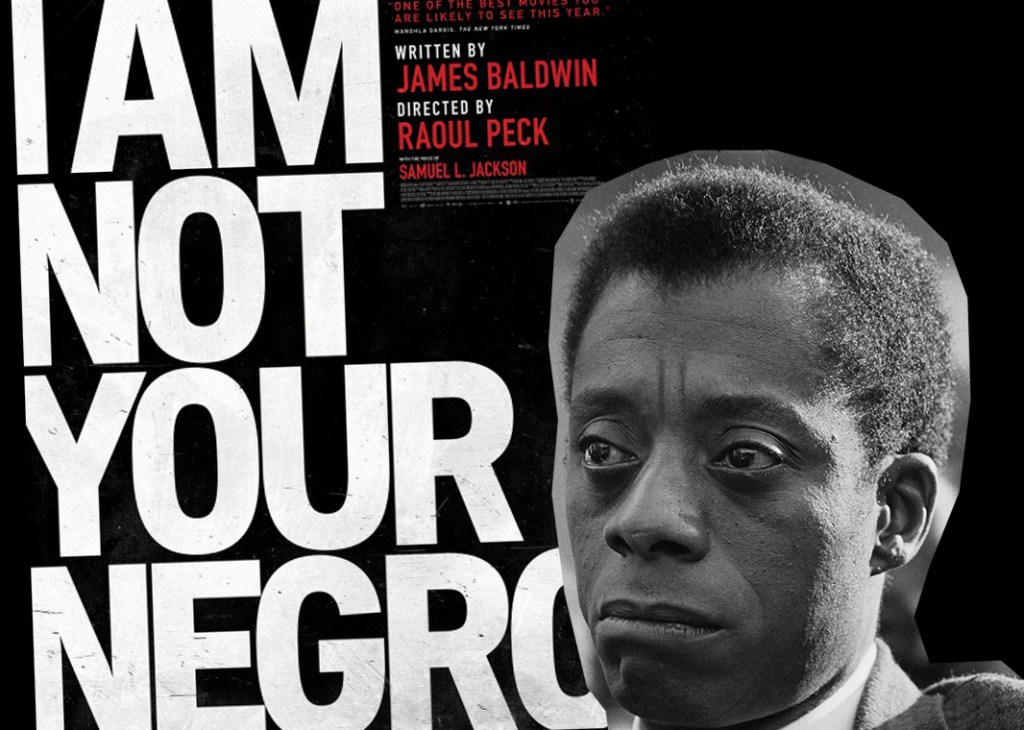

If 155 years seems like too long ago to imagine to start with, I have a recommendation for making history that is more recent come alive for you. Toni Morrison said of Between the World and Me, “I’ve been wondering who might fill the intellectual void that plagued me after James Baldwin died. Clearly it is Ta-Nehisi Coates.” Holy crap, man. What a review! Well, if you want to learn some more about history and its connection to the present, check out I Am Not Your Negro on HBO Now in the Black Lives Matter section. You can probably stream it too.

It is a 2016 documentary based on Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript Remember This House about his memories of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Medgar Evers. It is narrated by Samuel L Jackson, and it will blow your mind. So much of it is historical footage, a lot of the amazing James Baldwin and things you don’t want to believe happened like when Lorraine Hansberry, author of A Raisin in the Sun, asks John F Kennedy to go stand by and accompany Ruby Bridges, the little first grade girl who was the first black child to attend an integrated school in New Orleans while white people either fled or spat on her, and he replied that it would be “an empty symbolic act.” Shocking things like this where white people can really see that the things our people say and do today: the evasions, the minimizations, the disrespect and out-right lies come right out of the 60s. The 1960s and the 1860s. Start where you will. You will find it’s all there, still right with us in our house, waiting to be healed. Now that we’ve gotten a good start, let’s keep going and not stop.